For as long as I can remember, my self-worth has been embroidered on a label sewn into the backs of my clothing. The higher the number, the lower my head. The scale tells the story of my size and foretells the story of my mood.

My problems with weight began before high school, when girls competed by wearing Levi’s corduroys with the narrowest waist. I sucked in my stomach enough to fit a 28 when the popular girls were in a 26. I’d still be sucking it in today if I could. I wrote the following passages for a project called “Scale Stories” nearly a decade ago:

I sucked my stomach in from the time I was eleven until the time I was 35 and pregnant. You’d think those muscles would get strong in 24 years of sucking, but it only gives you a stomachache. Eventually, I got too fat to suck it in anymore.

In ninth grade, Miss Brown lined up all the girls. We wore snap-down, short, piss-yellow gym dresses with bulbous matching bloomers, which had the same skinny elastic at the waist and legs. The only thing that harmed your self-esteem more than catching a glimpse of yourself in your gym uniform was being weighed by Miss Brown.

I don’t remember whether she shouted out our numbers to a girl with a pad or whether she let us suffer a private humiliation, but I cried when I heard my number: 132. I was more than ten pounds heavier than my mother when she got married, and I wasn’t even in high school yet. One of the coolest girls in the whole school, Dawn, came over to me and consoled me by telling me that she weighed 138 pounds and that it was OK because we looked good. (She and I got our periods together in sixth grade; I think we were the only ones that year.) Dawn was an athlete. She was about three inches taller and had long, slender legs.

We had hardly ever spoken before or after that moment, but I never forgot her. It was easily the kindest thing anyone had ever said to me in all my years of grade school.

Yes, the kindest thing someone said to me in grade school was that she weighed more than I. To this day, I still size up a room—literally size it up by checking out the sizes of the people around me. Last year in New York, I was in a room with 19 people, and I was the fourth fattest: three men and one woman looked heavier.

Two years ago, I wrote:

I haven’t seen myself naked in 13 years.

I exaggerate. It’s only been about three years since I took a gander at my own naked reflection. When I emerge from the shower, I’m already tightly wrapped in a towel that I swear keeps shrinking in the wash. In the morning, I avert my eyes when I pass a mirror until most of my clothes are on. And when I finally do look, it’s to make sure that the only skin showing is below my elbow or (barely) above my cleavage.

That time I looked was the last time.

I have never liked my body. At its thinnest, my ankles were still fat; no matter how much I ran, I never got lean; my chest was too big.

I’ve never liked my body less than I like it right this moment.

I said that when I wrote this essay two years ago and again when I was going to post it last year and again now.

I say that every time I write about my weight. It is usually April, and I am usually dreading the season where everything shows—all the puckers and divots and wobbling flesh. All this despite my having reached the age of invisibility. You’d think this lovely, six-year-old cloak would bring me a new level of confidence and certainty I’d not experienced before, the freedom to walk about shoeless on concrete in nothing more than a tankini (well, tentini) and my signature necklace and nose hoop. But age has just exacerbated the feelings of valuelessness.

The writing about it is how you know I’ve bottomed out. I could look at all the great things my body’s done: it gets me from here to there and back to here again, it moves me up and down the stairs each day, carries my camera, hikes in the woods and sometimes up mountains (last summer, down and up and through canyons in Zion and Cedar Breaks), and stands long enough to fix dinner and bake cakes and challah.

But it’s not without a good bit of pain these days, as it’s plagued with slipped and herniated discs, pinched nerves, torn cuffs, sciatica, stenosis, and arthritis. My body has migraine and asthma. My shoulders have divots in the bone from carrying so much weight in my bra. So you could say I’m not a particularly grateful host.

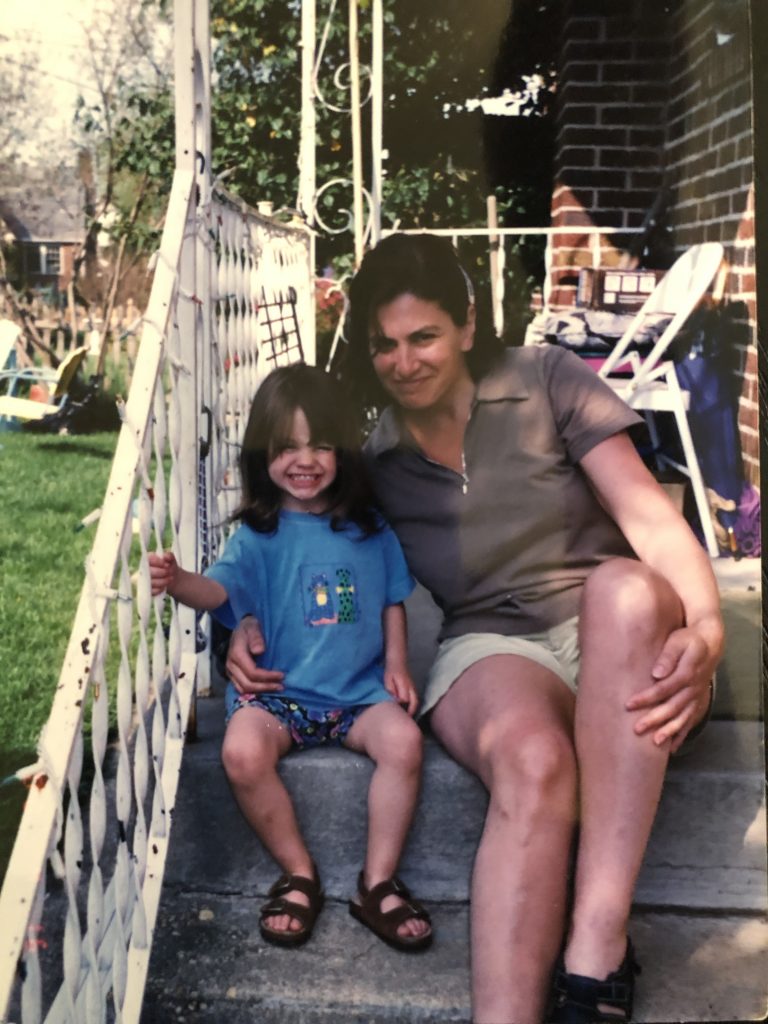

I have six photos called “I thought I was fat.” They were posted at various times throughout my 20 years on Flickr, without my even having recalled that I’d posted a previous photo with that title.

You’d think that after 40 years of dieting, I’d give it up already, that I’d recognize it doesn’t work. But the fact is that dieting does work! It works more than anything else you can do—more than pills, more than surgery, more than exercise (though exercise is great for everything). What doesn’t work is not dieting. Every single time I stop watching what I eat, my body manages to find its set point. Only now, my weight is limping up with every serving of Lexapro and Klonopin, holding on, unrelenting, to a single unplanned slice of cake, prioritizing it over two weeks of salad and lean meat.

The real issue is not how much I weigh. It’s how much extra I—and the people around me—suffer because of it.

If there’s a moral here, I don’t know it. Love the skin you’re in? Be grateful you can still tie your shoes? Eat ice cream? Go with the flow? I’m still searching for the magic pill that will take me back to my wedding weight of 144, back when I thought I was ten pounds too fat! Or else I should be searching for the magic No Fucks Given mind, which also gives me the gratitude and the ice cream.

Instead, it’s my 56th summer, and I’m still covering myself up, even in my own bedroom.