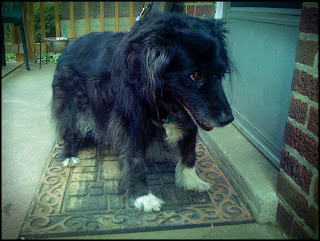

In the summer, we thought it might be time. Cleo was sleeping 23 hours a day, snoring loudly because of a thickening in her throat. She was suffering from arthritis, maybe a disc or other neurological issue. She was deaf, sometimes disoriented, incontinent with increasing frequency. It was difficult to wake her sometimes, and she was having trouble keeping her footing on the slippery tile floor. Then she couldn’t get up the steps by herself. Then she started falling down the stairs. We got a barrier and kept her on the first floor at night, but she’d stand at the bottom step and scratch on the makeshift gate for an hour. We’d sometimes give in, depending on the strength of Marty’s back. But she grew more restless at night and wandered the hallway, panting and knocking over things. She seemed to suffer from dementia and would get herself stuck under chairs or in corners, unable to back up—she’d just stand in the corner and pant.

My living room is now full of barriers—big foam core walls—to danger. I feared she’d burn herself on a floor lamp or start a fire with electrical cords. She got her head stuck between the fridge and the wall, where we stored some folding chairs; they tipped a little and seemed to pin her head—gently, but she didn’t know the difference.

Still, she seemed to enjoy going to the park and would often perk up to see Chance and Marty getting ready. She was always hungry, too, and didn’t that mean she still wanted to live? So that made it hard for us to agree on the time. Perhaps my family felt that my fear of a second back surgery (the first a result of having to lift Cleopatra each day to put her in the truck for a walk at the park) made me more eager to be rid of this physical burden—pulling her out of corners and lifting her onto her feet. And who could blame them for their love?

From the moment this five-month-old puppy wandered into our back yard in April of 1996, Cleopatra Queen-of-Denial Miller has been a loyal and delightful companion. Where Beowulf King-of-the-Geats Miller was a favorite among certain menfolk in our lives, Cleo was one of the most beloved dogs at the park. This is no hyperbole. Our dogsitter never charged us to watch her. My sister, who is highly allergic, would often bury her face in Cleo’s fur. My brother-in-law would have taken Cleo for his own, despite his wife’s allergies. In fact, we got a lot of similar offers. People loved our dogs so much that when Cleo had Beowulf’s puppies, our vet took one. A neighbor took two. We kept Buddha.

From the moment this five-month-old puppy wandered into our back yard in April of 1996, Cleopatra Queen-of-Denial Miller has been a loyal and delightful companion. Where Beowulf King-of-the-Geats Miller was a favorite among certain menfolk in our lives, Cleo was one of the most beloved dogs at the park. This is no hyperbole. Our dogsitter never charged us to watch her. My sister, who is highly allergic, would often bury her face in Cleo’s fur. My brother-in-law would have taken Cleo for his own, despite his wife’s allergies. In fact, we got a lot of similar offers. People loved our dogs so much that when Cleo had Beowulf’s puppies, our vet took one. A neighbor took two. We kept Buddha.

Cleo’s always told us what she wanted or needed. She’d scratch at the back door to go out or come in; she’d fetch sticks and drop them at our feet or put balls in our lap. She didn’t take no for an answer, either, and would bark at us or paw us until we played. She spoke in a sweet little trill, slept on her back with all four paws in the air, licked our faces, played a mean game of tug-o-war (often snatching sticks from other dogs). She never bit us, not even by accident. She was only really sick once—with Lyme disease. And she took care of us, waiting for whomever was trailing behind.

In the last few weeks, it’s been clear to me in her pleading eyes. I’ve been waiting for my husband’s realization to catch up with my own. We’ve done this before—lost three dogs and two cats during our twenty-eight-year relationship, never mind those pets that came and went before we met. So it was never a question of whether it was the right thing to do.

When our daughter, Serena, was born, Beowulf was dying from kidney disease. We were waiting for the sign that he was done, and it came on a cold February morning. Marty took Wulf to the picnic table outside and covered him, spoke to him, kept him warm with hugs while we waited for the vet to come to the house. The shot that usually goes to work in a few short seconds took more than two minutes to work. Wulf let out a howl that is forever etched in our memories. I let it get to me sometimes, let myself believe that Wulf was trying to stop us instead of thanking us for his wonderful life and saying goodbye. His body had completely shut down; he couldn’t even metabolize the euthanasia agent. No question it was the right thing.

When our daughter, Serena, was born, Beowulf was dying from kidney disease. We were waiting for the sign that he was done, and it came on a cold February morning. Marty took Wulf to the picnic table outside and covered him, spoke to him, kept him warm with hugs while we waited for the vet to come to the house. The shot that usually goes to work in a few short seconds took more than two minutes to work. Wulf let out a howl that is forever etched in our memories. I let it get to me sometimes, let myself believe that Wulf was trying to stop us instead of thanking us for his wonderful life and saying goodbye. His body had completely shut down; he couldn’t even metabolize the euthanasia agent. No question it was the right thing.

I had a feeling this final image was clouding my husband’s judgment, just as it haunted me. But Cleo’s decline over the last few days has been swift. She can no longer stand on her own and is often found trying to scramble away from her puddle of pee. When we stand her up and put her in the yard, she wanders around in crooked, slanted circles, stumbling. At least once every day, I am alone and having to wrap Cleo’s pee soaked body in my arms to move her. And she has finally lost her appetite. On Saturday, she refused her bone, and I called the vet.

It took that, I think—the indignity of lying in one’s own urine and excrement coupled with lack of a desire for food—to make her condition urgent. I have been crying, with small periods of clear speech (usually to yell at someone), since Saturday. Last night at midnight, I heard some furniture moving in the kitchen and rescued Cleo from what I hope and wish is her last puddle. I slept fitfully.

This morning, before he left for work, Marty stood in the kitchen and cried. If you think something is already a big pile sad, set a crying man on top. Serena left her homework in the dining room, so I took the opportunity at school to inform the staff that my people are fragile today. As if they couldn’t already tell.

This morning, before he left for work, Marty stood in the kitchen and cried. If you think something is already a big pile sad, set a crying man on top. Serena left her homework in the dining room, so I took the opportunity at school to inform the staff that my people are fragile today. As if they couldn’t already tell.

The vet will come tonight, and we will bury Cleo in the morning. This is as right as our hearts are broken. Our dogs have always been beloved members of our family. They celebrate our joys and comfort us in times of grief. When they go, pieces of us go with them.

Their people will be fragile for a little while.