(continued from part 1)

I am sitting in the lobby of Bob Schneider’s hotel, waiting for my favorite rock star to finish showering and get back into my car. As I say this, I still can’t believe Bob Schneider was just in the front seat of my car! It’s even more surreal than the time I touched Kip Winger’s stomach. I look in the bathroom mirror at my face. It’s older than it was this morning, and I have a bunch more new silver hairs sprouting from my center part. But I don’t bother with refreshment makeup or my hat. I find a giant round ottoman close to the coffee bar and try to stretch my still-crippled back by lounging. I imagine I look like a black widow stricken with the Cruciatus Curse—or, worse, like one of those sit-com women who tries to seduce a man by splaying herself atop a bed, putting her body in several awkward positions, eventually giving up and doing something hideous, at which time the boyfriend comes into the room. I prop myself against a mirrored column and call a friend.

I am sitting in the lobby of Bob Schneider’s hotel, waiting for my favorite rock star to finish showering and get back into my car. As I say this, I still can’t believe Bob Schneider was just in the front seat of my car! It’s even more surreal than the time I touched Kip Winger’s stomach. I look in the bathroom mirror at my face. It’s older than it was this morning, and I have a bunch more new silver hairs sprouting from my center part. But I don’t bother with refreshment makeup or my hat. I find a giant round ottoman close to the coffee bar and try to stretch my still-crippled back by lounging. I imagine I look like a black widow stricken with the Cruciatus Curse—or, worse, like one of those sit-com women who tries to seduce a man by splaying herself atop a bed, putting her body in several awkward positions, eventually giving up and doing something hideous, at which time the boyfriend comes into the room. I prop myself against a mirrored column and call a friend.

I’m a groupie. It doesn’t mean what you think: I am an appreciator, an aficionado, an enthusiast—at least when it comes to a few individual bands (most of whom are mentioned by name in the acknowledgments of The Book). I like seeing live bands more than I like food; indeed, I get through this entire day on a scrambled egg and some beer. I bask in the afterglow of sweaty rock stardom much the way Hendrix the Creature, our bearded dragon, basks on a rock: with his tongue out and a big snaggle-toothed grin.

I’m a groupie. It doesn’t mean what you think: I am an appreciator, an aficionado, an enthusiast—at least when it comes to a few individual bands (most of whom are mentioned by name in the acknowledgments of The Book). I like seeing live bands more than I like food; indeed, I get through this entire day on a scrambled egg and some beer. I bask in the afterglow of sweaty rock stardom much the way Hendrix the Creature, our bearded dragon, basks on a rock: with his tongue out and a big snaggle-toothed grin.

It’s not celebrity. I wouldn’t wait in line for an actor’s autograph; would not seek out the artist at an opening; don’t care much to meet my favorite writers (I would have my books signed if the line is short). It’s not about sex, either—at least I don’t think it’s about that, though who has not imagined making out with an attractive, talented, famous person (Bruce Springsteen comes to mind—a lot). Hell, I’ve thought about making out with Brandi Carlile, and I don’t even swing that way.

It’s not celebrity. I wouldn’t wait in line for an actor’s autograph; would not seek out the artist at an opening; don’t care much to meet my favorite writers (I would have my books signed if the line is short). It’s not about sex, either—at least I don’t think it’s about that, though who has not imagined making out with an attractive, talented, famous person (Bruce Springsteen comes to mind—a lot). Hell, I’ve thought about making out with Brandi Carlile, and I don’t even swing that way.

It’s music. Music makes me swoon. Music and lust and love are intertwined in an intoxicating three-way.

Maybe I think that rubbing elbows with talented people will take me back to when I fronted a band and performed every weekend for dancing crowds who knew the pretentious words to my eighties band’s songs (a time before we had computers, sonny). Or maybe all this psychoanalysis of my musical motives is bullshit, and I’m just an old band whore with a solid moral center and a flabby self-image.

When Bob comes down from showering (does he look even better with wet hair?), I barely see him because I’m trying to catch the score of the Ravens game, out of bored curiosity rather than concern. And I think it’s the first time Bob even looks at me, though it may be with a little bit of annoyance—I can’t tell. I just smile.

When Bob comes down from showering (does he look even better with wet hair?), I barely see him because I’m trying to catch the score of the Ravens game, out of bored curiosity rather than concern. And I think it’s the first time Bob even looks at me, though it may be with a little bit of annoyance—I can’t tell. I just smile.

We get in the car, and he wants to know about museums and galleries, and I give him as much of the scoop as I know about the Visionary and the probably-closed galleries up Charles Street, where I don’t take him, though I could easily have given him a brief tour. We had time. Instead, I turn down Light Street as he admires the bird skull I’d hung from the rearview—it replaced that awful blue and gold Goucher tassel. And now, because “where’d you get it?” inevitably leads to Marty, which leads to “what does he do,” which leads to my humorous-but-misrepresentational answer, that “he’s an atheist-communist teaching at a Catholic school,” I am sucked, and I mean shop-vac’d, into a discussion about God—or god, as it is in my case.

Oh, why couldn’t we be talking about his son’s little electric guitar or naming the album of songs left after my favorite ones were put on The Californian? (I suggest The Baltimorean, and he loves the sound of it, says it a couple of times, nods, “The Baltimorean, yeah!”)

Oh, why couldn’t we be talking about his son’s little electric guitar or naming the album of songs left after my favorite ones were put on The Californian? (I suggest The Baltimorean, and he loves the sound of it, says it a couple of times, nods, “The Baltimorean, yeah!”)

Without turning his head, Bob asks how a person arrives at that—at atheism. “It’s just another brand,” he tells me. Perhaps it would be, I argue, if we actually celebrated or reveled in the atheism, but we don’t. I’m looking straight ahead, like a deer in the headlights, but with a view of the Maryland Science Center and encroaching traffic. If I crash, it will be God’s fault. “Every religion known to man, from the ancient Egyptians to the present-day religions, is founded on Do Unto Others, and I think we know that moral code from birth. It’s innate. It’s why we feel bad when we hurt someone’s feelings. And those who don’t have that conscience turn out to be psychopaths and sociopaths. I don’t think god can save those people,” I say in similar words.

Is Bob answering me? I don’t know. I am busy rambling about how ridiculous it is that people who treat others with cruelty get to accept Jesus on their death beds and go to heaven. I talk about how I’d rather think of the pretty trees—which change color, lose leaves, come back with a whole new sense of tree-ness—as miracles and everything else man’s fault. Otherwise, if we give credit to a god for the good things, we have to blame him for the Holocaust and kidnapping and rape.

Is Bob answering me? I don’t know. I am busy rambling about how ridiculous it is that people who treat others with cruelty get to accept Jesus on their death beds and go to heaven. I talk about how I’d rather think of the pretty trees—which change color, lose leaves, come back with a whole new sense of tree-ness—as miracles and everything else man’s fault. Otherwise, if we give credit to a god for the good things, we have to blame him for the Holocaust and kidnapping and rape.

Poor Bob. He might as well be a member of my family now; he can’t get a word in edgewise. He tries to clarify that he’s against organized religion, that it’s just another “brand,” too; he is struggling not to be misunderstood. Or maybe he is listening and thinking. I can’t tell. I am absorbed in making the case for atheism, practically turning it into the irreligious conviction I had previously denied.

By the time we are at the venue, the conversation comes to a halt with the car, and I practically shove him out the door—“Out you go!” or “Well, here you are!”—and go to a bar to drink with the Raven maniacs.

Not exactly. First I make friends with a football-fan-hating cop, who allows me to park with my rear end hanging past the sign. Then I run into Harmoni while strolling back past the club. “There’s so much cool stuff,” she tells me while looking through a store window. She’s lamenting all the money she spends in cities before shows, and I ask what she can do besides shop. “I will sometimes go to a park and take pictures,” she says, and I tell her about the view from Federal Hill, about overlooking the Visionary Arts museum. I’m attempting to walk her out the door, maybe go with her to the hill, but she’s hinting that she’s a solo flyer, so I point in the general vicinity and take my cue to duck into the bar.

Not exactly. First I make friends with a football-fan-hating cop, who allows me to park with my rear end hanging past the sign. Then I run into Harmoni while strolling back past the club. “There’s so much cool stuff,” she tells me while looking through a store window. She’s lamenting all the money she spends in cities before shows, and I ask what she can do besides shop. “I will sometimes go to a park and take pictures,” she says, and I tell her about the view from Federal Hill, about overlooking the Visionary Arts museum. I’m attempting to walk her out the door, maybe go with her to the hill, but she’s hinting that she’s a solo flyer, so I point in the general vicinity and take my cue to duck into the bar.

I am on duty, but I’m waiting for sound check, which I expect to be between 4:30 and 5:00 and take about an hour. So a 3:00-ish Sierra Nevada is not irresponsible. I’d rather be eating sushi with the guitarist or on the hill with the bassist. After my beer, I charge my phone in the car, and talk to Marty and my sister, who wonders if Bob’ll do “Titty Bangin'” tonight, as if I could gauge that by our god discussion. I get Ted’s text, and I’m off to sound check.

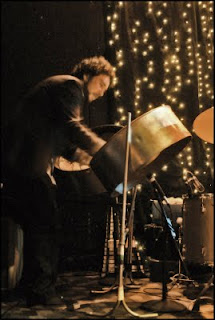

It’s uneventful at first—a lot of nnns and uuuuhs and “more monitor” and wire detanglement and cord arrangement, but eventually it’s time for drums, and Conrad Choucroun takes his spot at the kit. He looks up and sees me on the second floor. He waves. “Hi, Leslie!”

It’s uneventful at first—a lot of nnns and uuuuhs and “more monitor” and wire detanglement and cord arrangement, but eventually it’s time for drums, and Conrad Choucroun takes his spot at the kit. He looks up and sees me on the second floor. He waves. “Hi, Leslie!”

The whole world stops. Nothing else is happening. At all. (Hint to men: women like this.)

In a few minutes, I’m (mostly) over the flattery and taking pictures and even secretly, guiltily filming a little of the sound check. An hour later, when it’s all over, my handshake to Conrad is replied with a hug. Bob asks for dining advice, and Harmoni worries about time and a shower. Both she and Conrad walk to my car for a lift.

“So what are you working on now,” Conrad asks. “Another book?” I’m surprised. I didn’t tell anyone about the book—not Ted, not Bob. Perhaps they looked me up on Ted’s laptop, or maybe he looked over the summer, when I added him as a My Space “friend.” He wants to know if it’s a food book, but I say I’m over that and working on a book about going to rock and roll camp. I tell them how hot Kip Winger is in person, and then we segue to crime, and they want to know if it’s really like The Wire. I get graphic with my tale of the guy who died on my corner, how I watched the last blood gurgle from a murdered gang banger’s mouth on the corner of my street. I was robbed at gunpoint. And my parents were mugged and my mother beaten up in front of her house. And my sister was robbed at gunpoint at work. “But it’s not

so bad.”

I write my cell phone number on Conrad’s key envelope (he still hasn’t called), and I start the driving race—home to pick up Marty and Serena, to my mom’s to drop off Serena, back to the hotel to pick up Conrad and Harmoni. Uptown, across town, and downtown across town. I am there in 43 minutes, despite having to turn around to get Marty’s show ticket. I’m three minutes shy of my 7:00 promise, but my charges had only just come outside. When they get in, I apologize for scaring them out of their wits, and they both laugh, somewhat relieved; I might have really worried them. Then Marty does all the talking for the rest of the drive, asking the questions I should’ve asked—how long they’ve been playing, whether they like being in Bob’s band, where they live. Back at the 8×10, I get an excellent parking space, find my name on the guest list, and go inside to drink. I deserve it.

I write my cell phone number on Conrad’s key envelope (he still hasn’t called), and I start the driving race—home to pick up Marty and Serena, to my mom’s to drop off Serena, back to the hotel to pick up Conrad and Harmoni. Uptown, across town, and downtown across town. I am there in 43 minutes, despite having to turn around to get Marty’s show ticket. I’m three minutes shy of my 7:00 promise, but my charges had only just come outside. When they get in, I apologize for scaring them out of their wits, and they both laugh, somewhat relieved; I might have really worried them. Then Marty does all the talking for the rest of the drive, asking the questions I should’ve asked—how long they’ve been playing, whether they like being in Bob’s band, where they live. Back at the 8×10, I get an excellent parking space, find my name on the guest list, and go inside to drink. I deserve it.

The show’s opening act, One Eskimo, is like a slowed-down Phil Collins with one long, ethereal song performed by not one but four Eskimos with unusual hair. I drink two pints of ale during their short set (and get a third once Bob’s band comes out). Meanwhile, Marty is flirting with two blonds. He picks them up by telling them his wife drove Bob Schneider around all day, and one of them, the drunk dumb one who’s my new best friend, says he must really trust me to let me—his hot, young wife—do that.

Marty sits on a stool against the wall with his bleary eyes closed most of the night. I’m on the side of the stage with a couple of friends and have a good view of everyone except Harmoni and Ollie Steck, the horn player. Only once during the show does the front man look my way, and when he does, there’s a slight smile of recognition. Bob is Bob. He sings great, cusses, gets crude, and peforms what I call “The Pussy Song.” I don’t like it, but it dispels any rumors that he’s really become Daddy Man, making his songs and shows safe for Rachel Ray’s viewers. Actually, Bob’s usual audience is probably those very same viewers—women who love it when someone talks dirty to them. The men love him, too, for getting to say all the things they’d like to but would get slapped for. And he warms up their females. A Bob Schneider show is all the foreplay most people need.

I don’t get a chance to shout out my favorite song, “Game Plan,” and that’s OK because Bob plays “The Hulk.” I yell a thank-you afterward, as if my liking the song in the car that afternoon reminded him to play it.

The show lasts about two hours, by which time I’ve had three pints of beer and leave without my Frunk or any goodbyes, except a text to Teddy asking him to save me a CD of the show. Marty drives us home, and we both agree it was one of Bob Schneider’s best, most hard-rocking shows. That’s all we say to each other. And while my husband is upstairs asleep at midnight, I eat leftover lasagna and think of all the things I should’ve done differently—from my fashion choices to the quality and quantity of my conversation. My biggest regret is not getting any casual, daylight, non-concert photos, for fear I’d look like a fan instead of a professional rock ‘n’ roll driver.

The show lasts about two hours, by which time I’ve had three pints of beer and leave without my Frunk or any goodbyes, except a text to Teddy asking him to save me a CD of the show. Marty drives us home, and we both agree it was one of Bob Schneider’s best, most hard-rocking shows. That’s all we say to each other. And while my husband is upstairs asleep at midnight, I eat leftover lasagna and think of all the things I should’ve done differently—from my fashion choices to the quality and quantity of my conversation. My biggest regret is not getting any casual, daylight, non-concert photos, for fear I’d look like a fan instead of a professional rock ‘n’ roll driver.

I also regret not using this perfect reply when Bob asked what my husband did for a living: “Oh, he’s a titty banger from way back.”