On Saturday morning, while my husband and daughter share cinnamon Bismarcks and chocolate donuts, I am getting intimate with a roll of paper towels and a bottle of glass cleaner in my car. I wipe away a year—that’s when my car was last cleaned, just before back surgery—of dog noses from the rear window, grime and bird shit and squashed bugs from the rest. I scoop up piles of hair and lint from the vinyl stick shift bag. I put away CDs that might be embarrassing, stick down a dashboard hula given to me months ago, and scrape off the entire cast of Sesame Street, save Elmo, applied for then-two-year-old Serena; I still love the furry red monster, and I do a wicked impersonation of his R-rated off-camera commentary (“Boys and girls, Elmo needs a cigarette and a six pack real bad”). I take my graduation tassel down; it was only there to hold the pen, which had long been missing. I throw away a ripped road atlas and a mountain of gum wrappers.

On Saturday morning, while my husband and daughter share cinnamon Bismarcks and chocolate donuts, I am getting intimate with a roll of paper towels and a bottle of glass cleaner in my car. I wipe away a year—that’s when my car was last cleaned, just before back surgery—of dog noses from the rear window, grime and bird shit and squashed bugs from the rest. I scoop up piles of hair and lint from the vinyl stick shift bag. I put away CDs that might be embarrassing, stick down a dashboard hula given to me months ago, and scrape off the entire cast of Sesame Street, save Elmo, applied for then-two-year-old Serena; I still love the furry red monster, and I do a wicked impersonation of his R-rated off-camera commentary (“Boys and girls, Elmo needs a cigarette and a six pack real bad”). I take my graduation tassel down; it was only there to hold the pen, which had long been missing. I throw away a ripped road atlas and a mountain of gum wrappers.

That I was cleaning my ten-year-old Pathfinder could only mean one thing. Somebody important was getting in it.

I had volunteered to be a runner for Bob Schneider’s band—someone who would take them where they needed to go—places like the hotel and the venue. I forgot about hating driving, erased the fact that my daughter’s first cuss word was in imitation of me yelling at other drivers, dismissed the thought that it could be a nightmare with a Ravens game, already well attended but even more serious with their nemesis, the Colts, in town. But I said yes and wondered how I’d break it to my husband—who has seen about seven years of my bad behavior at Bob shows—that my fantasy might be sitting in my front seat.

My husband feigns hurt that I would clean the car for Bob but not for him or our daughter, yet on Sunday, he takes over the shop vac, sucking up every speck of dog hair from the car’s floors and seats and head rests. He can’t help it. He loves Bob, too.

It’s probably an odd thing for a forty-(inaudible mumbling)-year -old woman to be doing on a Sunday from noon to eight p.m., during her daughter’s last soccer game. It’s a task that requires several days of advance preparation, what with clothes shopping, dieting, and hair straightening. I’ve been told I do weird things, that I “squeeze the fun out of life.” (I’m not sure whether this means I kill it with strangulation or suck out its best juices.) But I write what I know, and there’s only so much knowing you can do sitting at the kitchen table with your laptop. And there isn’t much I wouldn’t do for good music. I do not, however, dress on Sunday morning in anything that plunges. I do not, as my sister and husband both suggested, pack a change of underwear. I do not wear my BABY, HERE’S YOUR GAME PLAN t-shirt. I’m in the Threadless haiku tee and black cords, my usual brown cowboy boots, my old Indian hat, and a black jacket. My hair is straight.

It’s probably an odd thing for a forty-(inaudible mumbling)-year -old woman to be doing on a Sunday from noon to eight p.m., during her daughter’s last soccer game. It’s a task that requires several days of advance preparation, what with clothes shopping, dieting, and hair straightening. I’ve been told I do weird things, that I “squeeze the fun out of life.” (I’m not sure whether this means I kill it with strangulation or suck out its best juices.) But I write what I know, and there’s only so much knowing you can do sitting at the kitchen table with your laptop. And there isn’t much I wouldn’t do for good music. I do not, however, dress on Sunday morning in anything that plunges. I do not, as my sister and husband both suggested, pack a change of underwear. I do not wear my BABY, HERE’S YOUR GAME PLAN t-shirt. I’m in the Threadless haiku tee and black cords, my usual brown cowboy boots, my old Indian hat, and a black jacket. My hair is straight.

I had what I thought to be a pretty realistic grasp on what runner detail would entail: I might take Harmoni Kelly, the bass player, to buy a new lipstick; shuttle Conrad Choucroun between hotel and venue; hunt down several cans of Rockstar Energy; separate and remove all the green M&Ms, because surely Bob doesn’t need to get hornier. I couldn’t imagine what I’d do with the front man in the front seat of my SUV; I doubted he’d even get in my car.

My first assignment, from a sleepy Ted Roberson, tour manager, is to deliver Ted and Eric-the-bus-driver to the hotel from the 8×10. I stand outside the bus and wait for them to emerge, pack them up, move them out. When we arrive at the hotel (which hotel is privileged information), Eric tells me he is pleasantly surprised to find a woman driving a stick shift and a truck. Ladies don’t roll like that in Texas, apparently.

The second unglamorous order of business is helping Ted get a new laptop plug from to the Towson Apple store. It is a ten-mile schlep, and the tour manager, who is, follicle-ly at least, nearly identical to a young Bob Ross (he of “happy trees” fame) is friendly but not exactly a self-starter in the talk arena. First I offer him a red-hot atomic fireball; I’d jammed a whole box of them in the side pocket of my door because they’re great appetite suppressants. Ted turns his head slowly, like I’d somehow turned into Afro-dite, like the atomic fireball was only the best edible confection known to man. He holds out his hand to receive the individually wrapped, irresistible red tongue burner (and, careful, tooth breaker). Then I entertain him with exciting tales of my guitar prodigy daughter, my thoughts about Billy Harvey having made a mistake leaving Bob’s band, and my opinion about Bob Schneider’s latest album, the cuss-less Lovely Creatures. Ted says that many fans have conjectured that foul language (songs like “Titty Bangin’” are always crowd pleasers) was holding him back from national recognition. But the real reason for this change is Bob’s four-year-old son, which has made him more sensitive to how he behaves in the world. Bah. I don’t know Bob, but I don’t buy it. I think he’ll always know when it’s inappropriate to be inappropriate. I pray to the music spirit that Bob does what I call “The Pussy Song” tonight—just as a sign that this Daddy Virus hasn’t affected his gauge.

The second unglamorous order of business is helping Ted get a new laptop plug from to the Towson Apple store. It is a ten-mile schlep, and the tour manager, who is, follicle-ly at least, nearly identical to a young Bob Ross (he of “happy trees” fame) is friendly but not exactly a self-starter in the talk arena. First I offer him a red-hot atomic fireball; I’d jammed a whole box of them in the side pocket of my door because they’re great appetite suppressants. Ted turns his head slowly, like I’d somehow turned into Afro-dite, like the atomic fireball was only the best edible confection known to man. He holds out his hand to receive the individually wrapped, irresistible red tongue burner (and, careful, tooth breaker). Then I entertain him with exciting tales of my guitar prodigy daughter, my thoughts about Billy Harvey having made a mistake leaving Bob’s band, and my opinion about Bob Schneider’s latest album, the cuss-less Lovely Creatures. Ted says that many fans have conjectured that foul language (songs like “Titty Bangin’” are always crowd pleasers) was holding him back from national recognition. But the real reason for this change is Bob’s four-year-old son, which has made him more sensitive to how he behaves in the world. Bah. I don’t know Bob, but I don’t buy it. I think he’ll always know when it’s inappropriate to be inappropriate. I pray to the music spirit that Bob does what I call “The Pussy Song” tonight—just as a sign that this Daddy Virus hasn’t affected his gauge.

Serena, almost twelve, has been a Bob fan for most of her life, and let me tell you it was quite a feat quick-turning the volume up and down in anticipation of the fucks and shits and motherfuckers on nearly every record (but especially The Californian, my personal favorite). Eventually, I let the songs play thinking she wouldn’t notice, but she did. For awhile, she’d cover her ears until the offensive word had passed. But soon she just started singing along with “The Sons of Ralph,” and it was all over. (I have a recording of Serena, 9, and my nephew, Graham, 7, singing “Party at the Neighbors.” It’s a testament to the ageless appeal of the Bob.)

Ted thinks his boss will be a household name (and not just in my house) in about six months from a combination of good airplay and his guest appearance on Rachel Ray in early November. He sure holds sway with middle-aged buxom brunettes. By the end of our twenty miles, after discussing Ted’s work as a sound engineer and Bob’s lunatic fan base, we are back at the bus. I tell him I’ll hang around Federal Hill so that I can see sound check, though parking is ridiculous during game day. After about ten minutes of riding up and down the same four blocks, I finally come upon someone leaving at 1:45. That’s when my phone buzzes with a text: “Hey, bob would like to go to hotel before load in. I would say within the next 30 minutes. If you could be available to run him over that would be great.”

Bob. The hotel. Bahhhhhhhb.

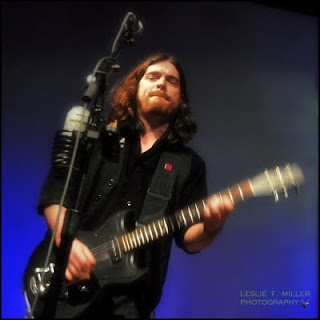

I find guitarist Billy Cassis on the corner with Ted searching for any glimpse of Bob, who has wandered up Cross Street in road-trip haze. “You know what it’s like to be driving in the bus all night and wake up in the morning and just wander out into a strange place, not knowing where you’re going,” he says. I don’t. I usually wake up and bolt out of bed, fresh and alert, I tell him. But yeah, I do understand. You go on the inertia of road hum. Billy was with Bob on the summer tour, replacing Jeff Plankenhorn, a guy so brilliant that he deserves the cover of Guitar Player. Like Billy Harvey before him, Plank left the backup band to attend to personal projects.

I find guitarist Billy Cassis on the corner with Ted searching for any glimpse of Bob, who has wandered up Cross Street in road-trip haze. “You know what it’s like to be driving in the bus all night and wake up in the morning and just wander out into a strange place, not knowing where you’re going,” he says. I don’t. I usually wake up and bolt out of bed, fresh and alert, I tell him. But yeah, I do understand. You go on the inertia of road hum. Billy was with Bob on the summer tour, replacing Jeff Plankenhorn, a guy so brilliant that he deserves the cover of Guitar Player. Like Billy Harvey before him, Plank left the backup band to attend to personal projects.

Cassis is only about my height, handsome, with a soft voice similar to that of Billy Harvey. He is both funny about and sensitive to an elderly lady on the street. She’s carrying a grocery bag with Charmin in it, and she looks lost. I’m a little worried that it’s me in a few years—some old ho hanging around a tour bus in front of a nightclub, wishing she had misspent more of her youth.

Bassist Harmoni Kelley returns from wandering the neighborhood and is excited about a thrift shop purchase. Billy thinks that place might have something that matches my own style and tries to sell me on a trip there, but I’m a working girl after all. And I have a Bob Job.

I move my car to the alley, half on the sidewalk, and wait for the man who finally comes in the crosshairs, heading toward us in Chuck Taylors and his FAYM (short for Fuck All You Motherfuckers, of course) hoodie, carrying an issue of The Goon under his arm from a visit to a comic book store. In the daylight, without the drama of darkness and ale, without the magic of crude lyrics and one of the best rock voices a person could hope to hear, he’s just sort of a boy. I move my car off the sidewalk so he can get in, and we go, a little quietly at first. He asks what I do. Well, I drive rock stars around—and apparently not well. A cab has stopped in the street, and I try to go around him, but the light changes too quickly, and I have to back up out of the lane of oncoming traffic. Something like this has to happen when you’re with someone you like. (For years I’d see a secret crush, and I’d always be in sweats with a bad cold and messy hair.)

I tell Bob I’m a writer and a photographer. He wants to know what I write, and I do not tell him that I wrote the book I gave him last time—I don’t want him to think I had any fantasies that he’d have read it or even cracked it open to see whatever I’d scrawled in pink marker to him after I’d had a pint of Smithwicks before the Annapolis show over the summer. It’s not really a man’s book, after all. And it’s certainly no Goon. So I tell him I’m working on a book about rock camps, and I brag on my daughter some more. At one point, I joke: “Now that I have you in my car—“ but he looks a little squeamish, so I just ask what was up when he wrote the songs from The Californian, songs that are entirely different from his usual repertoire. But he was not, as I’d suspected, going through some manic phase (like I was at the time of its release). It was more like what happens when a praying mantis dies and goes into overdrive. It was Billy Harvey’s last album, and it was going to be recorded live in the studio, using all of Billy’s best Billy-ness to go out with a bang and a double-record set. But a friend listened to it and said, “Why not put all these hard rock songs on one album?” So he did.

I tell Bob I’m a writer and a photographer. He wants to know what I write, and I do not tell him that I wrote the book I gave him last time—I don’t want him to think I had any fantasies that he’d have read it or even cracked it open to see whatever I’d scrawled in pink marker to him after I’d had a pint of Smithwicks before the Annapolis show over the summer. It’s not really a man’s book, after all. And it’s certainly no Goon. So I tell him I’m working on a book about rock camps, and I brag on my daughter some more. At one point, I joke: “Now that I have you in my car—“ but he looks a little squeamish, so I just ask what was up when he wrote the songs from The Californian, songs that are entirely different from his usual repertoire. But he was not, as I’d suspected, going through some manic phase (like I was at the time of its release). It was more like what happens when a praying mantis dies and goes into overdrive. It was Billy Harvey’s last album, and it was going to be recorded live in the studio, using all of Billy’s best Billy-ness to go out with a bang and a double-record set. But a friend listened to it and said, “Why not put all these hard rock songs on one album?” So he did.

Bob doesn’t do a lot of those songs at shows anymore. He stopped doing my favorite, “Game Plan,” in favor of the title track. “I have so many songs,” he tells me, including the ones he hasn’t even put on a record yet. But he fears he’s getting a little like his dad, a musician who had a huge repertoire and one day just started playing the same twelve songs over and over again. I think at some point my daughter is going to say that about her father, who is now in his Pink Floyd and Yes phase of guitarring in the kitchen. I ask about his son, who likes to sing in his home studio and wonder about the song he inspired and “cowrote” with his dad, “The Hulk.”

“I don’t do that song anymore,” he says, almost wistfully.

“I like that song a lot,” I say, wistfully.

We’re at the hotel, so I help him get his key from the front desk, and I sit down to update my Facebook status—something like “is at the hotel with Bob while he showers. In the lobby. Hooray for clean. Boo for lobby.” But really—hooray for the lobby. And hooray for finding my own way here, to this point in my life.

To be continued.

(Next: God is Bob’s friend, and drummer Conrad Choucroun is mine.)

*Kissy-face-Bob manipulation by Steve Parke